-

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 201 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 202 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 203 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 204 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 205 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 206 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 207 / 591 sold -

Sewing parties were common back when most women sewed blankets, quilts and clothing. This solid oak portable sewing table is in fine condition to use as it was purposed or as a side table to display photos or collectibles. A handy measuring guide is etched into the table. The Clean Cut antique fabric cutter works great and slices right through fabric. The legs of the table fold easily for compact transport. 208 / 591 sold -

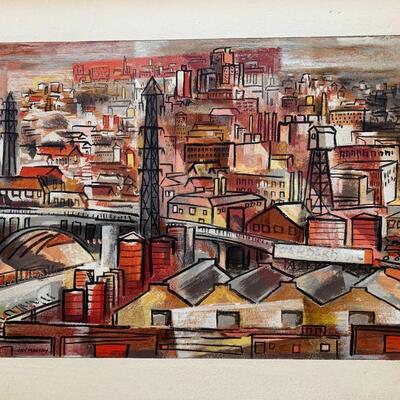

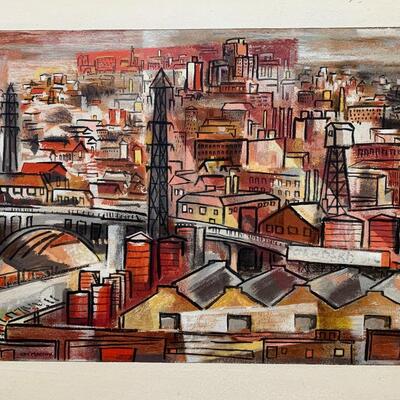

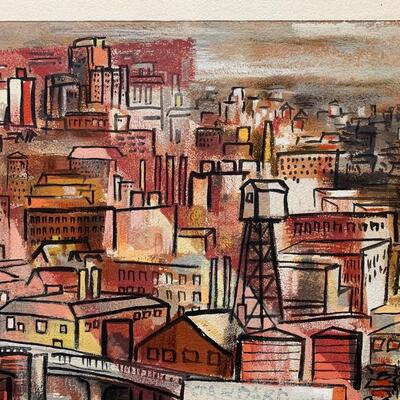

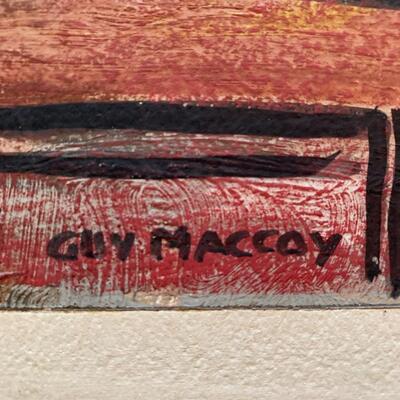

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 212 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 213 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 214 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 215 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 216 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 217 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 218 / 591 sold -

A fabulous find with a low starting price! This awesome Guy Maccoy serigraph is a city scape , maybe Cleveland? In the lower right quadrant of the serigraph you can read a faded Standard Oil billboard . Rockefeller owned Standard Oil Refinery and it was based out of Cleveland, Ohio. Not sure if Maccoy was making a statement by "fading out" the way the billboard once read. Standard Oil. According to encyclopedia Britannica, "In 1911, after dissolution of the Standard Oil empire, eight companies retained “Standard Oil†in their names, but by the late 20th century the name had almost passed into history." Nevertheless, the is a classic piece of mid century art! Scroll down to read more about Guy Maccoy. \/ Buyer pays shipping and handling. The dimensions of the Maccoy serigraph: Frame is 44 5/8" wide x 35 1/8" tall Serigraph is 29 3/4" wide x 20" tall Born Valley Falls, Oct. 7, 1904 and died Los Angeles, CA, Mar. 18, 1981, Guy Maccoy was a painter, printmaker and teacher. He studied at the Kansas City Art Institute from 1924-28; in Colorado Springs; and, after moving to New York, at the Art Students League and at Columbia University. He was a pupil of John Douglas Patrick, William Rosenbauer, Alexander Kostellow, and Anthony Angarola. He worked as a supervisor in the Federal Art Project. Maccoy moved to Los Angeles in 1947 and cofounded the Western Serigraph Society. He taught at the Otis Art Institute until retirement in 1965. 219 / 591 sold -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 220 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 221 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 222 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 223 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 224 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 225 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 226 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 227 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 228 / 591 -

Wow! What a great find! And somewhat rare! This gorgeous ornate brass parlor clock is still ticking! What a wonderful asset to bring to the fireplace mantle or the shelf in the gentleman's quarters of the hunting lodge. Late 19th or early 20th century. Clock measures: 14" width x 16" height x 5" depth Happy bidding! Buyer pays shipping and handling. 229 / 591 -

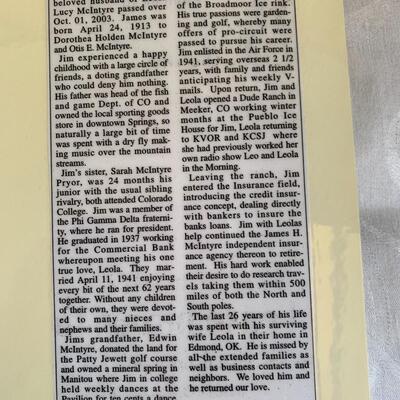

Its more than 120 years old! And it comes from the estate of the grandson of the original owner of Manitou Springs. Read the 4th paragraph of the obituary (pictured). In the picture of the three men, Edwin is on the far right, his son Otic is in the middle and James is far left. Buyer pays shipping and handling. Happy bidding. 240 / 591 sold -

Its more than 120 years old! And it comes from the estate of the grandson of the original owner of Manitou Springs. Read the 4th paragraph of the obituary (pictured). In the picture of the three men, Edwin is on the far right, his son Otic is in the middle and James is far left. Buyer pays shipping and handling. Happy bidding. 241 / 591 sold -

Its more than 120 years old! And it comes from the estate of the grandson of the original owner of Manitou Springs. Read the 4th paragraph of the obituary (pictured). In the picture of the three men, Edwin is on the far right, his son Otic is in the middle and James is far left. Buyer pays shipping and handling. Happy bidding. 242 / 591 sold -

Its more than 120 years old! And it comes from the estate of the grandson of the original owner of Manitou Springs. Read the 4th paragraph of the obituary (pictured). In the picture of the three men, Edwin is on the far right, his son Otic is in the middle and James is far left. Buyer pays shipping and handling. Happy bidding. 243 / 591 sold -

Its more than 120 years old! And it comes from the estate of the grandson of the original owner of Manitou Springs. Read the 4th paragraph of the obituary (pictured). In the picture of the three men, Edwin is on the far right, his son Otic is in the middle and James is far left. Buyer pays shipping and handling. Happy bidding. 244 / 591 sold -

Its more than 120 years old! And it comes from the estate of the grandson of the original owner of Manitou Springs. Read the 4th paragraph of the obituary (pictured). In the picture of the three men, Edwin is on the far right, his son Otic is in the middle and James is far left. Buyer pays shipping and handling. Happy bidding. 245 / 591 sold -

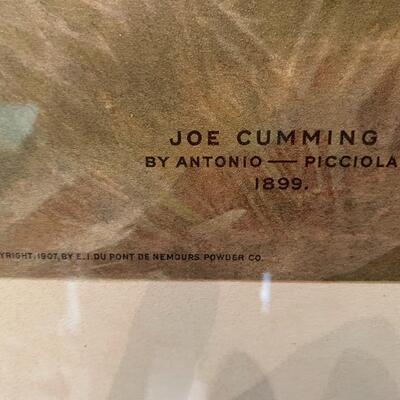

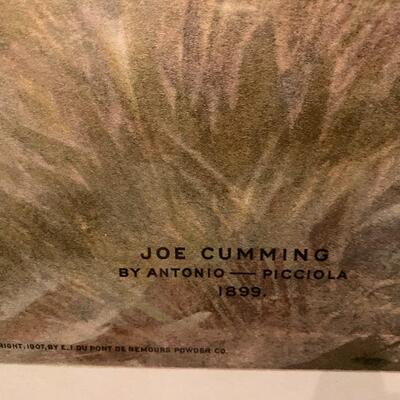

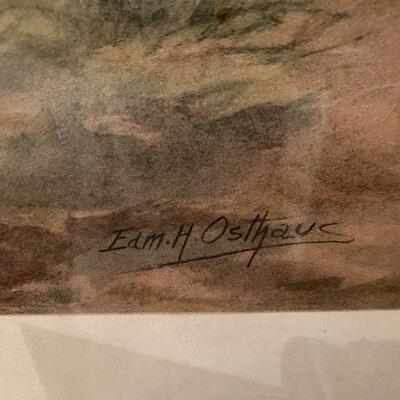

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 246 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 247 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 248 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 249 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 250 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 251 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 252 / 591 -

Antique Edmond H. Osthaus hunting dog lithograph signed by artist Edm. H. Osthaus. Titled "Joe Cumming by Antonio-Picciola-1899" In right hand corner is signature of artist. Copyright 1907 by E.F. DuPont De Memours Powder Co. Item is excellent condition. Frame appears to be walnut and upon close examination, has a couple scuffs, otherwise overall condition is SUBERB! Print/Litho measures: 22" width x 16" height Frame measures: 35 1/2" width x 25 1/2" height 253 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 254 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 255 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 256 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 257 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 258 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 259 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 260 / 591 -

Lot of 7 antique cast iron trivets. 261 / 591 -

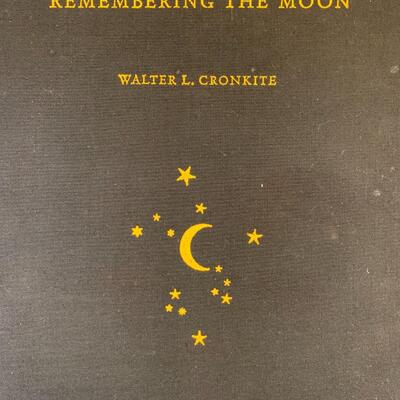

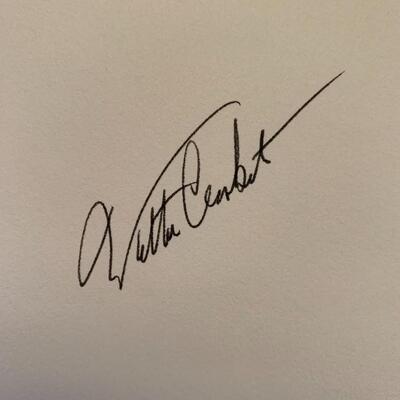

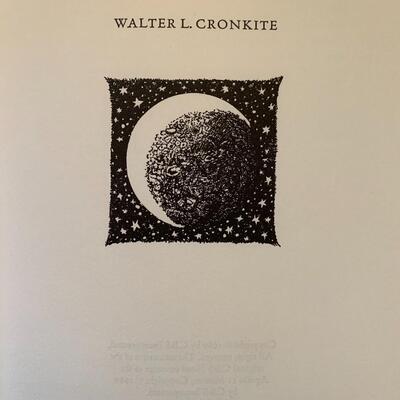

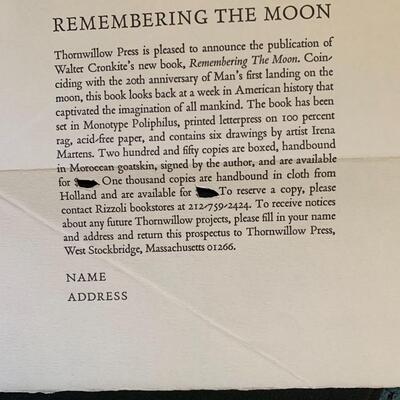

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of Man's first landing on the moon, this book looks back at a week in American history that captivated the imagination of all mankind. From a limited edition of 1000 copies hand-bound in cloth from Holland. Autographed by Walter Cronkite. Prices on Amazon range from $125-$718. 275 / 591 -

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of Man's first landing on the moon, this book looks back at a week in American history that captivated the imagination of all mankind. From a limited edition of 1000 copies hand-bound in cloth from Holland. Autographed by Walter Cronkite. Prices on Amazon range from $125-$718. 276 / 591 -

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of Man's first landing on the moon, this book looks back at a week in American history that captivated the imagination of all mankind. From a limited edition of 1000 copies hand-bound in cloth from Holland. Autographed by Walter Cronkite. Prices on Amazon range from $125-$718. 277 / 591 -

Coinciding with the 20th anniversary of Man's first landing on the moon, this book looks back at a week in American history that captivated the imagination of all mankind. From a limited edition of 1000 copies hand-bound in cloth from Holland. Autographed by Walter Cronkite. Prices on Amazon range from $125-$718. 278 / 591 -

Swan Rubber Company used to have a manufacturing plant in Stillwater, OK. The plant closed in the 1970's a;nd Armstrong Industries purchased the building. In the demolition and conversion process, the giant Swan was removed from the face of the building and kept safe for 40+ years. Swan measures: 5' height x 5' wide x 6-8" depth (approx) 295 / 591 -

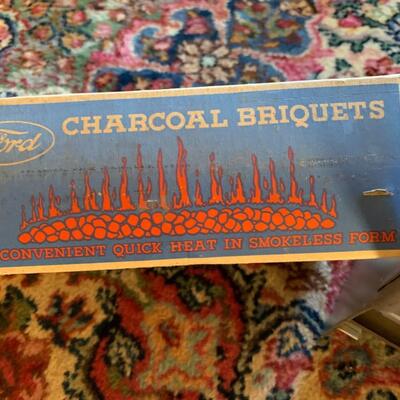

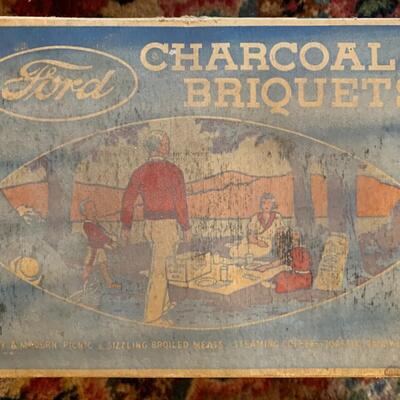

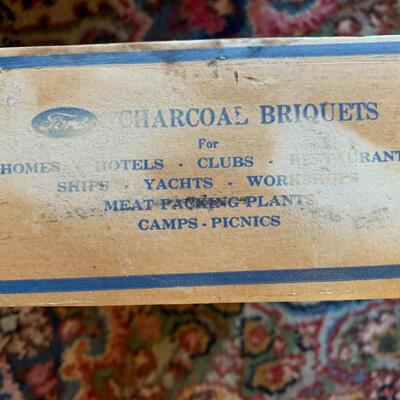

Never used. Mint condition. Henry Ford is associated with a lot of things, most famously modernizing the production of the automobile by using a cost-saving assembly line process and bringing motorized transportation to the masses. Somewhat less famously, Henry Ford was stringently cheap, saving pennies and fractions of pennies anyway he could. Even less famously, this frugalness led Henry Ford down a path of invention and construction that has fueled—quite literally—America’s obsession with outside grilling. Grille vs Grill While most people think of grill*e*s when talking of Ford, this is regarding grills (No E). Fittingly enough, Henry Ford’s connection with grilling began on a camping trip. Beginning in 1915, and persisting for the next decade, Henry Ford took annual summer camping trips with a group known as the Vagabonds. Consisting of Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and famed conservationist John Burroughs as the main members, these camping trips went to exotic locales such as the Everglades or the Catskill Mountains; they even once visited the sitting American President Coolidge at his personal home in Vermont. Four Vagabonds The Four Vagabonds. Over the years these trips grew, and various people were invited on them. One such lucky individual was Henry Ford’s cousin’s husband, Edward G. Kingsford. Ford was building more and more Model T’s, and wanted to begin supplying all the wood he needed on his own. As each Model T used over 100ft of wood—wheels, frames, seats, many parts—Henry Ford would need a lot of trees, and the means to harvest them. E.G. Kingsford stepped up to the plate for his new cousin, as he was fortuitously a real estate agent. Brokering the purchase of over 313,000 acres of lumber in Michigan’s northern peninsula, Kingsford continued to be of use in developing the land. Building sawmills for the lumber solved one problem, yet Ford needed workers to staff his new mills, and so he tasked Kingsford with the building of a small town, aptly named Kingsford, Michigan. Sawmill An unused postcard touting the success of Ford’s Michigan sawmill. E.G. Kingsford had helped Henry Ford in meeting his own demand for lumber, and yet Ford was still not pleased. Looking to save costs anyway he could, he had built a new parts and body factory at the location of the sawmill, to reduce transportation costs. While effective, Ford found that these new factories had a few unavoidable wastes, such as wood chippings, trimmings, and shavings. When parts and cars are built in the millions, apparently these trimmings add up to a noticeable amount: at least to Henry Ford. By 1922, the Ford Motor Company calculated that the lost value of this wood was around $11,000 a day; allegedly the bean-counters even took the sawdust from the mills into account. Ford Sawmill Ford’s sawmill, busy *wasting* wood by turning it into sawdust c. 1921. While the accountants were finding out the value of the waste, Henry Ford had tasked a chemist by the name of Orin Stafford to come up with a means to salvage the waste and turn it into a measurable value. Stafford achieved this by turning mill waste—such as sawdust and chippings—into small lumps of dark fuel: the charcoal briquette. Achieved by mixing wood products with tar and cornstarch, Ford realized that he could market the product, and began preparations for a new plant to be built in Kingsford. Fellow Vagabond Thomas Edison lent a hand to his old pal Ford, and helped in designing the plant which was to be placed next to the sawmill and parts factory. Titled the Carbonization Building, this plant began construction in 1922, with operation beginning in 1924. Able to process all of the day’s waste, the Carbonization plant broke down waste wood into usable components through refinement and distillation. For every ton of scrap that entered the building, Ford could eke out 135 pounds of acetate lime, 61 gallons of wood alcohol, 15 gallons of tar and other various oils, 600 cubic feet of fuel gas—used to power the surrounding plants—and finally 610 pounds of charcoal. Carbonization building The Carbonization building and its storage silos, in full-force. June 30, 1925. While Ford could use many of the by-products of this process, he could not use all the charcoal that he was producing. Sure enough, Ol’ Henry Ford couldn’t let anything go to waste, and soon enough Ford dealers across the nation were selling charcoal-powered grills, and the briquets—Ford shortened the word for ease of use—to fuel them. Header A Ford charcoal grill and box of charcoal briquets. Henry Ford made one small miscalculation: the American buying public wasn’t keen on the idea of outdoor cooking during the Depression, around when the Ford briquet was introduced. For many American’s, cooking outdoors was a matter of necessity and not a choice of leisure activity. Sales could charitably be called ‘slow’. At the outbreak of World War II, Henry Ford was still making briquets in an attempt to curb waste. While the factories in Kingsford were busy producing wood-paneled station wagons and replacement car parts, this would soon change. Almost the entire Kingsford plant location began to fuel the war effort, producing B-24 Liberator’s, as well as the engines to accompany them. Willow Run The B-24 Liberator factory, called Willow Run. This production almost entirely utilized both Ford’s workforce and lumber supply. After the war, production began to shift away from implements of war and back towards civilian ‘Woodie’ vans and other wooden car parts. With this shift, the growing stockpile of briquets were again a waiting asset to be sold. Luckily for Ford, societal factors were beginning to shift in the favor of outdoor grilling. With the growing number of suburbia-based families, many began looking for a way to reconnect with nature and escape the growing cement monster of towns and cities. While this in itself may not have been enough to spark the grilling craze, the fortuitous invention of the Weber grill cemented the practice as a piece of Americana. Original Weber The first Weber grill was made in 1952, produced by cutting a buoy in half and topping it to trap in the grill-y goodness. Soon, families were popping burgers on their new Weber, with Ford made briquets underneath. In honor of the help Kingsford provided Ford—both the man and the company—Henry Ford renamed the briquet business Kingsford Charcoal, a familiar name today. Eventually, as the operation began to turn a profit, Ford sold the operation to the Clorox company, who kept the Kingsford name. To this day, the Kingsford briquets that fuel most of America’s grills can trace their lineage to the penny-pinching tendencies of one man: Henry Ford. 296 / 591 -

Never used. Mint condition. Henry Ford is associated with a lot of things, most famously modernizing the production of the automobile by using a cost-saving assembly line process and bringing motorized transportation to the masses. Somewhat less famously, Henry Ford was stringently cheap, saving pennies and fractions of pennies anyway he could. Even less famously, this frugalness led Henry Ford down a path of invention and construction that has fueled—quite literally—America’s obsession with outside grilling. Grille vs Grill While most people think of grill*e*s when talking of Ford, this is regarding grills (No E). Fittingly enough, Henry Ford’s connection with grilling began on a camping trip. Beginning in 1915, and persisting for the next decade, Henry Ford took annual summer camping trips with a group known as the Vagabonds. Consisting of Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and famed conservationist John Burroughs as the main members, these camping trips went to exotic locales such as the Everglades or the Catskill Mountains; they even once visited the sitting American President Coolidge at his personal home in Vermont. Four Vagabonds The Four Vagabonds. Over the years these trips grew, and various people were invited on them. One such lucky individual was Henry Ford’s cousin’s husband, Edward G. Kingsford. Ford was building more and more Model T’s, and wanted to begin supplying all the wood he needed on his own. As each Model T used over 100ft of wood—wheels, frames, seats, many parts—Henry Ford would need a lot of trees, and the means to harvest them. E.G. Kingsford stepped up to the plate for his new cousin, as he was fortuitously a real estate agent. Brokering the purchase of over 313,000 acres of lumber in Michigan’s northern peninsula, Kingsford continued to be of use in developing the land. Building sawmills for the lumber solved one problem, yet Ford needed workers to staff his new mills, and so he tasked Kingsford with the building of a small town, aptly named Kingsford, Michigan. Sawmill An unused postcard touting the success of Ford’s Michigan sawmill. E.G. Kingsford had helped Henry Ford in meeting his own demand for lumber, and yet Ford was still not pleased. Looking to save costs anyway he could, he had built a new parts and body factory at the location of the sawmill, to reduce transportation costs. While effective, Ford found that these new factories had a few unavoidable wastes, such as wood chippings, trimmings, and shavings. When parts and cars are built in the millions, apparently these trimmings add up to a noticeable amount: at least to Henry Ford. By 1922, the Ford Motor Company calculated that the lost value of this wood was around $11,000 a day; allegedly the bean-counters even took the sawdust from the mills into account. Ford Sawmill Ford’s sawmill, busy *wasting* wood by turning it into sawdust c. 1921. While the accountants were finding out the value of the waste, Henry Ford had tasked a chemist by the name of Orin Stafford to come up with a means to salvage the waste and turn it into a measurable value. Stafford achieved this by turning mill waste—such as sawdust and chippings—into small lumps of dark fuel: the charcoal briquette. Achieved by mixing wood products with tar and cornstarch, Ford realized that he could market the product, and began preparations for a new plant to be built in Kingsford. Fellow Vagabond Thomas Edison lent a hand to his old pal Ford, and helped in designing the plant which was to be placed next to the sawmill and parts factory. Titled the Carbonization Building, this plant began construction in 1922, with operation beginning in 1924. Able to process all of the day’s waste, the Carbonization plant broke down waste wood into usable components through refinement and distillation. For every ton of scrap that entered the building, Ford could eke out 135 pounds of acetate lime, 61 gallons of wood alcohol, 15 gallons of tar and other various oils, 600 cubic feet of fuel gas—used to power the surrounding plants—and finally 610 pounds of charcoal. Carbonization building The Carbonization building and its storage silos, in full-force. June 30, 1925. While Ford could use many of the by-products of this process, he could not use all the charcoal that he was producing. Sure enough, Ol’ Henry Ford couldn’t let anything go to waste, and soon enough Ford dealers across the nation were selling charcoal-powered grills, and the briquets—Ford shortened the word for ease of use—to fuel them. Header A Ford charcoal grill and box of charcoal briquets. Henry Ford made one small miscalculation: the American buying public wasn’t keen on the idea of outdoor cooking during the Depression, around when the Ford briquet was introduced. For many American’s, cooking outdoors was a matter of necessity and not a choice of leisure activity. Sales could charitably be called ‘slow’. At the outbreak of World War II, Henry Ford was still making briquets in an attempt to curb waste. While the factories in Kingsford were busy producing wood-paneled station wagons and replacement car parts, this would soon change. Almost the entire Kingsford plant location began to fuel the war effort, producing B-24 Liberator’s, as well as the engines to accompany them. Willow Run The B-24 Liberator factory, called Willow Run. This production almost entirely utilized both Ford’s workforce and lumber supply. After the war, production began to shift away from implements of war and back towards civilian ‘Woodie’ vans and other wooden car parts. With this shift, the growing stockpile of briquets were again a waiting asset to be sold. Luckily for Ford, societal factors were beginning to shift in the favor of outdoor grilling. With the growing number of suburbia-based families, many began looking for a way to reconnect with nature and escape the growing cement monster of towns and cities. While this in itself may not have been enough to spark the grilling craze, the fortuitous invention of the Weber grill cemented the practice as a piece of Americana. Original Weber The first Weber grill was made in 1952, produced by cutting a buoy in half and topping it to trap in the grill-y goodness. Soon, families were popping burgers on their new Weber, with Ford made briquets underneath. In honor of the help Kingsford provided Ford—both the man and the company—Henry Ford renamed the briquet business Kingsford Charcoal, a familiar name today. Eventually, as the operation began to turn a profit, Ford sold the operation to the Clorox company, who kept the Kingsford name. To this day, the Kingsford briquets that fuel most of America’s grills can trace their lineage to the penny-pinching tendencies of one man: Henry Ford. 297 / 591 -

Never used. Mint condition. Henry Ford is associated with a lot of things, most famously modernizing the production of the automobile by using a cost-saving assembly line process and bringing motorized transportation to the masses. Somewhat less famously, Henry Ford was stringently cheap, saving pennies and fractions of pennies anyway he could. Even less famously, this frugalness led Henry Ford down a path of invention and construction that has fueled—quite literally—America’s obsession with outside grilling. Grille vs Grill While most people think of grill*e*s when talking of Ford, this is regarding grills (No E). Fittingly enough, Henry Ford’s connection with grilling began on a camping trip. Beginning in 1915, and persisting for the next decade, Henry Ford took annual summer camping trips with a group known as the Vagabonds. Consisting of Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and famed conservationist John Burroughs as the main members, these camping trips went to exotic locales such as the Everglades or the Catskill Mountains; they even once visited the sitting American President Coolidge at his personal home in Vermont. Four Vagabonds The Four Vagabonds. Over the years these trips grew, and various people were invited on them. One such lucky individual was Henry Ford’s cousin’s husband, Edward G. Kingsford. Ford was building more and more Model T’s, and wanted to begin supplying all the wood he needed on his own. As each Model T used over 100ft of wood—wheels, frames, seats, many parts—Henry Ford would need a lot of trees, and the means to harvest them. E.G. Kingsford stepped up to the plate for his new cousin, as he was fortuitously a real estate agent. Brokering the purchase of over 313,000 acres of lumber in Michigan’s northern peninsula, Kingsford continued to be of use in developing the land. Building sawmills for the lumber solved one problem, yet Ford needed workers to staff his new mills, and so he tasked Kingsford with the building of a small town, aptly named Kingsford, Michigan. Sawmill An unused postcard touting the success of Ford’s Michigan sawmill. E.G. Kingsford had helped Henry Ford in meeting his own demand for lumber, and yet Ford was still not pleased. Looking to save costs anyway he could, he had built a new parts and body factory at the location of the sawmill, to reduce transportation costs. While effective, Ford found that these new factories had a few unavoidable wastes, such as wood chippings, trimmings, and shavings. When parts and cars are built in the millions, apparently these trimmings add up to a noticeable amount: at least to Henry Ford. By 1922, the Ford Motor Company calculated that the lost value of this wood was around $11,000 a day; allegedly the bean-counters even took the sawdust from the mills into account. Ford Sawmill Ford’s sawmill, busy *wasting* wood by turning it into sawdust c. 1921. While the accountants were finding out the value of the waste, Henry Ford had tasked a chemist by the name of Orin Stafford to come up with a means to salvage the waste and turn it into a measurable value. Stafford achieved this by turning mill waste—such as sawdust and chippings—into small lumps of dark fuel: the charcoal briquette. Achieved by mixing wood products with tar and cornstarch, Ford realized that he could market the product, and began preparations for a new plant to be built in Kingsford. Fellow Vagabond Thomas Edison lent a hand to his old pal Ford, and helped in designing the plant which was to be placed next to the sawmill and parts factory. Titled the Carbonization Building, this plant began construction in 1922, with operation beginning in 1924. Able to process all of the day’s waste, the Carbonization plant broke down waste wood into usable components through refinement and distillation. For every ton of scrap that entered the building, Ford could eke out 135 pounds of acetate lime, 61 gallons of wood alcohol, 15 gallons of tar and other various oils, 600 cubic feet of fuel gas—used to power the surrounding plants—and finally 610 pounds of charcoal. Carbonization building The Carbonization building and its storage silos, in full-force. June 30, 1925. While Ford could use many of the by-products of this process, he could not use all the charcoal that he was producing. Sure enough, Ol’ Henry Ford couldn’t let anything go to waste, and soon enough Ford dealers across the nation were selling charcoal-powered grills, and the briquets—Ford shortened the word for ease of use—to fuel them. Header A Ford charcoal grill and box of charcoal briquets. Henry Ford made one small miscalculation: the American buying public wasn’t keen on the idea of outdoor cooking during the Depression, around when the Ford briquet was introduced. For many American’s, cooking outdoors was a matter of necessity and not a choice of leisure activity. Sales could charitably be called ‘slow’. At the outbreak of World War II, Henry Ford was still making briquets in an attempt to curb waste. While the factories in Kingsford were busy producing wood-paneled station wagons and replacement car parts, this would soon change. Almost the entire Kingsford plant location began to fuel the war effort, producing B-24 Liberator’s, as well as the engines to accompany them. Willow Run The B-24 Liberator factory, called Willow Run. This production almost entirely utilized both Ford’s workforce and lumber supply. After the war, production began to shift away from implements of war and back towards civilian ‘Woodie’ vans and other wooden car parts. With this shift, the growing stockpile of briquets were again a waiting asset to be sold. Luckily for Ford, societal factors were beginning to shift in the favor of outdoor grilling. With the growing number of suburbia-based families, many began looking for a way to reconnect with nature and escape the growing cement monster of towns and cities. While this in itself may not have been enough to spark the grilling craze, the fortuitous invention of the Weber grill cemented the practice as a piece of Americana. Original Weber The first Weber grill was made in 1952, produced by cutting a buoy in half and topping it to trap in the grill-y goodness. Soon, families were popping burgers on their new Weber, with Ford made briquets underneath. In honor of the help Kingsford provided Ford—both the man and the company—Henry Ford renamed the briquet business Kingsford Charcoal, a familiar name today. Eventually, as the operation began to turn a profit, Ford sold the operation to the Clorox company, who kept the Kingsford name. To this day, the Kingsford briquets that fuel most of America’s grills can trace their lineage to the penny-pinching tendencies of one man: Henry Ford. 298 / 591 -

Never used. Mint condition. Henry Ford is associated with a lot of things, most famously modernizing the production of the automobile by using a cost-saving assembly line process and bringing motorized transportation to the masses. Somewhat less famously, Henry Ford was stringently cheap, saving pennies and fractions of pennies anyway he could. Even less famously, this frugalness led Henry Ford down a path of invention and construction that has fueled—quite literally—America’s obsession with outside grilling. Grille vs Grill While most people think of grill*e*s when talking of Ford, this is regarding grills (No E). Fittingly enough, Henry Ford’s connection with grilling began on a camping trip. Beginning in 1915, and persisting for the next decade, Henry Ford took annual summer camping trips with a group known as the Vagabonds. Consisting of Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and famed conservationist John Burroughs as the main members, these camping trips went to exotic locales such as the Everglades or the Catskill Mountains; they even once visited the sitting American President Coolidge at his personal home in Vermont. Four Vagabonds The Four Vagabonds. Over the years these trips grew, and various people were invited on them. One such lucky individual was Henry Ford’s cousin’s husband, Edward G. Kingsford. Ford was building more and more Model T’s, and wanted to begin supplying all the wood he needed on his own. As each Model T used over 100ft of wood—wheels, frames, seats, many parts—Henry Ford would need a lot of trees, and the means to harvest them. E.G. Kingsford stepped up to the plate for his new cousin, as he was fortuitously a real estate agent. Brokering the purchase of over 313,000 acres of lumber in Michigan’s northern peninsula, Kingsford continued to be of use in developing the land. Building sawmills for the lumber solved one problem, yet Ford needed workers to staff his new mills, and so he tasked Kingsford with the building of a small town, aptly named Kingsford, Michigan. Sawmill An unused postcard touting the success of Ford’s Michigan sawmill. E.G. Kingsford had helped Henry Ford in meeting his own demand for lumber, and yet Ford was still not pleased. Looking to save costs anyway he could, he had built a new parts and body factory at the location of the sawmill, to reduce transportation costs. While effective, Ford found that these new factories had a few unavoidable wastes, such as wood chippings, trimmings, and shavings. When parts and cars are built in the millions, apparently these trimmings add up to a noticeable amount: at least to Henry Ford. By 1922, the Ford Motor Company calculated that the lost value of this wood was around $11,000 a day; allegedly the bean-counters even took the sawdust from the mills into account. Ford Sawmill Ford’s sawmill, busy *wasting* wood by turning it into sawdust c. 1921. While the accountants were finding out the value of the waste, Henry Ford had tasked a chemist by the name of Orin Stafford to come up with a means to salvage the waste and turn it into a measurable value. Stafford achieved this by turning mill waste—such as sawdust and chippings—into small lumps of dark fuel: the charcoal briquette. Achieved by mixing wood products with tar and cornstarch, Ford realized that he could market the product, and began preparations for a new plant to be built in Kingsford. Fellow Vagabond Thomas Edison lent a hand to his old pal Ford, and helped in designing the plant which was to be placed next to the sawmill and parts factory. Titled the Carbonization Building, this plant began construction in 1922, with operation beginning in 1924. Able to process all of the day’s waste, the Carbonization plant broke down waste wood into usable components through refinement and distillation. For every ton of scrap that entered the building, Ford could eke out 135 pounds of acetate lime, 61 gallons of wood alcohol, 15 gallons of tar and other various oils, 600 cubic feet of fuel gas—used to power the surrounding plants—and finally 610 pounds of charcoal. Carbonization building The Carbonization building and its storage silos, in full-force. June 30, 1925. While Ford could use many of the by-products of this process, he could not use all the charcoal that he was producing. Sure enough, Ol’ Henry Ford couldn’t let anything go to waste, and soon enough Ford dealers across the nation were selling charcoal-powered grills, and the briquets—Ford shortened the word for ease of use—to fuel them. Header A Ford charcoal grill and box of charcoal briquets. Henry Ford made one small miscalculation: the American buying public wasn’t keen on the idea of outdoor cooking during the Depression, around when the Ford briquet was introduced. For many American’s, cooking outdoors was a matter of necessity and not a choice of leisure activity. Sales could charitably be called ‘slow’. At the outbreak of World War II, Henry Ford was still making briquets in an attempt to curb waste. While the factories in Kingsford were busy producing wood-paneled station wagons and replacement car parts, this would soon change. Almost the entire Kingsford plant location began to fuel the war effort, producing B-24 Liberator’s, as well as the engines to accompany them. Willow Run The B-24 Liberator factory, called Willow Run. This production almost entirely utilized both Ford’s workforce and lumber supply. After the war, production began to shift away from implements of war and back towards civilian ‘Woodie’ vans and other wooden car parts. With this shift, the growing stockpile of briquets were again a waiting asset to be sold. Luckily for Ford, societal factors were beginning to shift in the favor of outdoor grilling. With the growing number of suburbia-based families, many began looking for a way to reconnect with nature and escape the growing cement monster of towns and cities. While this in itself may not have been enough to spark the grilling craze, the fortuitous invention of the Weber grill cemented the practice as a piece of Americana. Original Weber The first Weber grill was made in 1952, produced by cutting a buoy in half and topping it to trap in the grill-y goodness. Soon, families were popping burgers on their new Weber, with Ford made briquets underneath. In honor of the help Kingsford provided Ford—both the man and the company—Henry Ford renamed the briquet business Kingsford Charcoal, a familiar name today. Eventually, as the operation began to turn a profit, Ford sold the operation to the Clorox company, who kept the Kingsford name. To this day, the Kingsford briquets that fuel most of America’s grills can trace their lineage to the penny-pinching tendencies of one man: Henry Ford. 299 / 591 -

Never used. Mint condition. Henry Ford is associated with a lot of things, most famously modernizing the production of the automobile by using a cost-saving assembly line process and bringing motorized transportation to the masses. Somewhat less famously, Henry Ford was stringently cheap, saving pennies and fractions of pennies anyway he could. Even less famously, this frugalness led Henry Ford down a path of invention and construction that has fueled—quite literally—America’s obsession with outside grilling. Grille vs Grill While most people think of grill*e*s when talking of Ford, this is regarding grills (No E). Fittingly enough, Henry Ford’s connection with grilling began on a camping trip. Beginning in 1915, and persisting for the next decade, Henry Ford took annual summer camping trips with a group known as the Vagabonds. Consisting of Ford, Thomas Edison, Harvey Firestone, and famed conservationist John Burroughs as the main members, these camping trips went to exotic locales such as the Everglades or the Catskill Mountains; they even once visited the sitting American President Coolidge at his personal home in Vermont. Four Vagabonds The Four Vagabonds. Over the years these trips grew, and various people were invited on them. One such lucky individual was Henry Ford’s cousin’s husband, Edward G. Kingsford. Ford was building more and more Model T’s, and wanted to begin supplying all the wood he needed on his own. As each Model T used over 100ft of wood—wheels, frames, seats, many parts—Henry Ford would need a lot of trees, and the means to harvest them. E.G. Kingsford stepped up to the plate for his new cousin, as he was fortuitously a real estate agent. Brokering the purchase of over 313,000 acres of lumber in Michigan’s northern peninsula, Kingsford continued to be of use in developing the land. Building sawmills for the lumber solved one problem, yet Ford needed workers to staff his new mills, and so he tasked Kingsford with the building of a small town, aptly named Kingsford, Michigan. Sawmill An unused postcard touting the success of Ford’s Michigan sawmill. E.G. Kingsford had helped Henry Ford in meeting his own demand for lumber, and yet Ford was still not pleased. Looking to save costs anyway he could, he had built a new parts and body factory at the location of the sawmill, to reduce transportation costs. While effective, Ford found that these new factories had a few unavoidable wastes, such as wood chippings, trimmings, and shavings. When parts and cars are built in the millions, apparently these trimmings add up to a noticeable amount: at least to Henry Ford. By 1922, the Ford Motor Company calculated that the lost value of this wood was around $11,000 a day; allegedly the bean-counters even took the sawdust from the mills into account. Ford Sawmill Ford’s sawmill, busy *wasting* wood by turning it into sawdust c. 1921. While the accountants were finding out the value of the waste, Henry Ford had tasked a chemist by the name of Orin Stafford to come up with a means to salvage the waste and turn it into a measurable value. Stafford achieved this by turning mill waste—such as sawdust and chippings—into small lumps of dark fuel: the charcoal briquette. Achieved by mixing wood products with tar and cornstarch, Ford realized that he could market the product, and began preparations for a new plant to be built in Kingsford. Fellow Vagabond Thomas Edison lent a hand to his old pal Ford, and helped in designing the plant which was to be placed next to the sawmill and parts factory. Titled the Carbonization Building, this plant began construction in 1922, with operation beginning in 1924. Able to process all of the day’s waste, the Carbonization plant broke down waste wood into usable components through refinement and distillation. For every ton of scrap that entered the building, Ford could eke out 135 pounds of acetate lime, 61 gallons of wood alcohol, 15 gallons of tar and other various oils, 600 cubic feet of fuel gas—used to power the surrounding plants—and finally 610 pounds of charcoal. Carbonization building The Carbonization building and its storage silos, in full-force. June 30, 1925. While Ford could use many of the by-products of this process, he could not use all the charcoal that he was producing. Sure enough, Ol’ Henry Ford couldn’t let anything go to waste, and soon enough Ford dealers across the nation were selling charcoal-powered grills, and the briquets—Ford shortened the word for ease of use—to fuel them. Header A Ford charcoal grill and box of charcoal briquets. Henry Ford made one small miscalculation: the American buying public wasn’t keen on the idea of outdoor cooking during the Depression, around when the Ford briquet was introduced. For many American’s, cooking outdoors was a matter of necessity and not a choice of leisure activity. Sales could charitably be called ‘slow’. At the outbreak of World War II, Henry Ford was still making briquets in an attempt to curb waste. While the factories in Kingsford were busy producing wood-paneled station wagons and replacement car parts, this would soon change. Almost the entire Kingsford plant location began to fuel the war effort, producing B-24 Liberator’s, as well as the engines to accompany them. Willow Run The B-24 Liberator factory, called Willow Run. This production almost entirely utilized both Ford’s workforce and lumber supply. After the war, production began to shift away from implements of war and back towards civilian ‘Woodie’ vans and other wooden car parts. With this shift, the growing stockpile of briquets were again a waiting asset to be sold. Luckily for Ford, societal factors were beginning to shift in the favor of outdoor grilling. With the growing number of suburbia-based families, many began looking for a way to reconnect with nature and escape the growing cement monster of towns and cities. While this in itself may not have been enough to spark the grilling craze, the fortuitous invention of the Weber grill cemented the practice as a piece of Americana. Original Weber The first Weber grill was made in 1952, produced by cutting a buoy in half and topping it to trap in the grill-y goodness. Soon, families were popping burgers on their new Weber, with Ford made briquets underneath. In honor of the help Kingsford provided Ford—both the man and the company—Henry Ford renamed the briquet business Kingsford Charcoal, a familiar name today. Eventually, as the operation began to turn a profit, Ford sold the operation to the Clorox company, who kept the Kingsford name. To this day, the Kingsford briquets that fuel most of America’s grills can trace their lineage to the penny-pinching tendencies of one man: Henry Ford. 300 / 591

Photos 201 - 300 of 591

Per page: