-

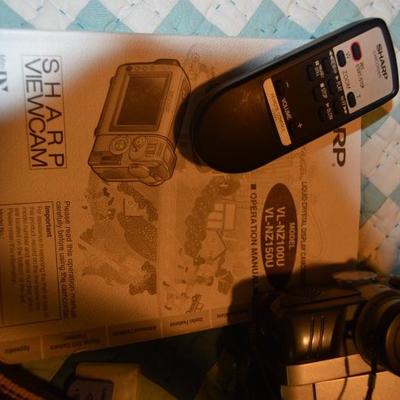

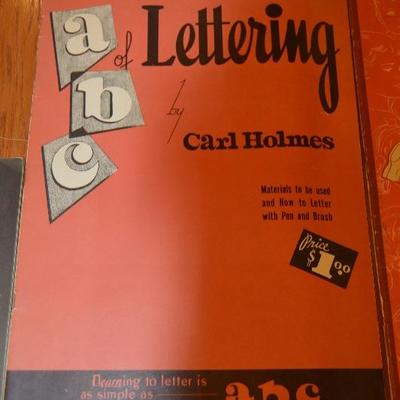

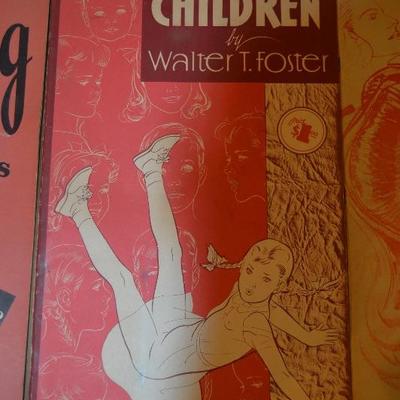

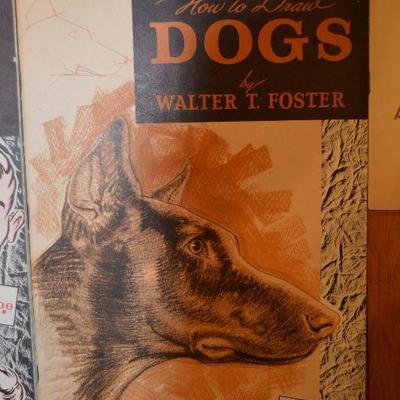

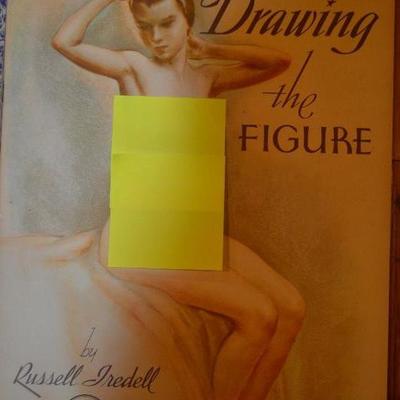

Both in excellent condition. 802 / 1073 -

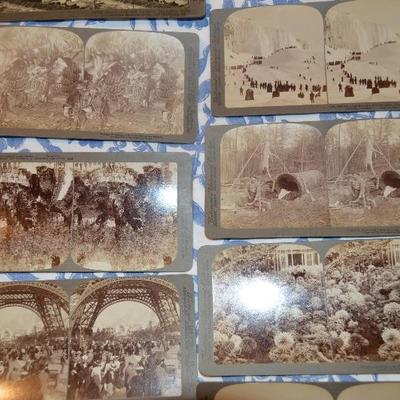

Both in excellent condition. 803 / 1073 -

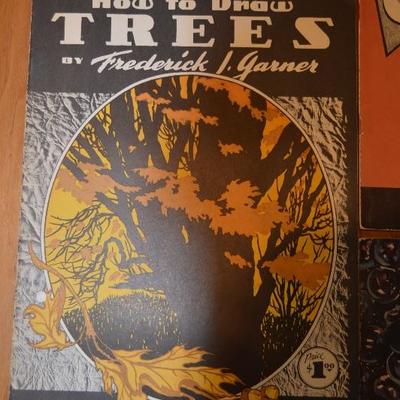

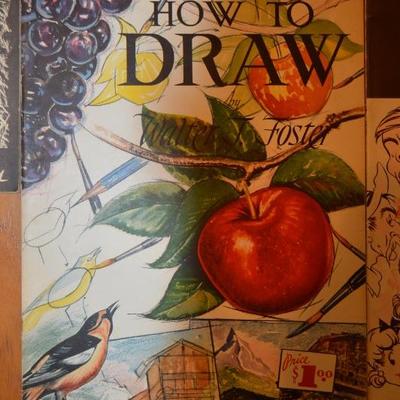

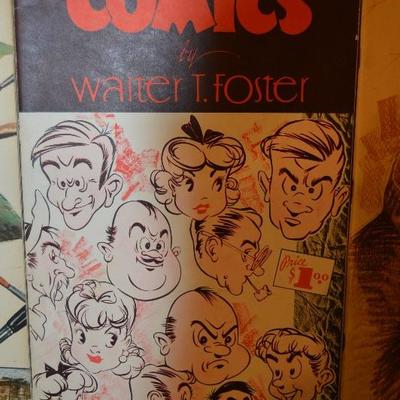

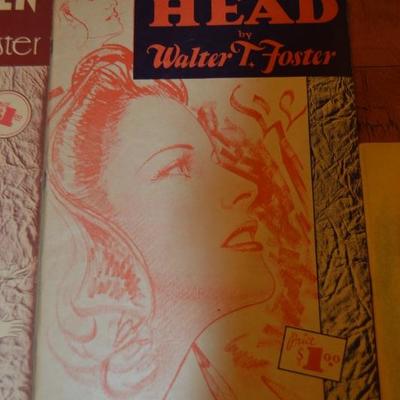

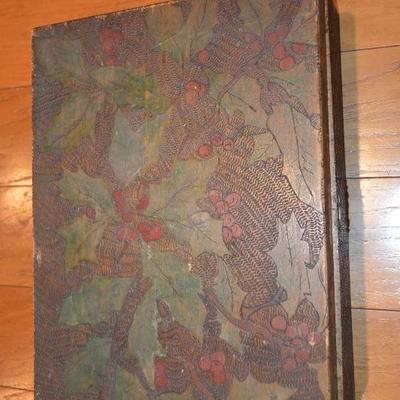

Both in excellent condition. 804 / 1073 -

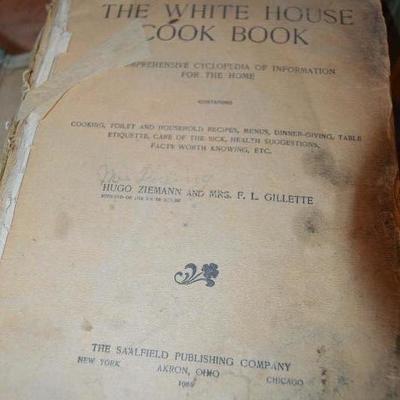

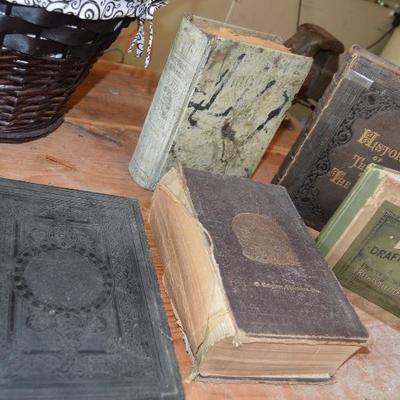

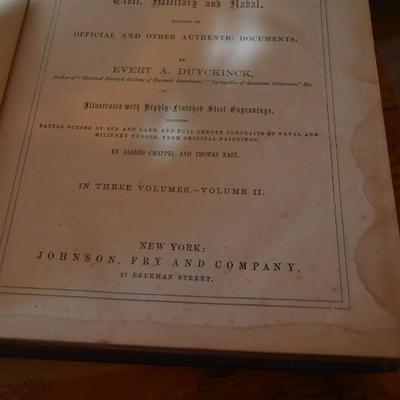

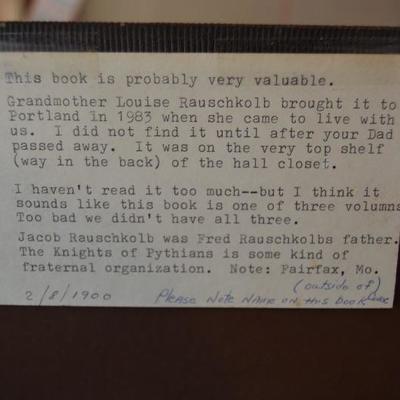

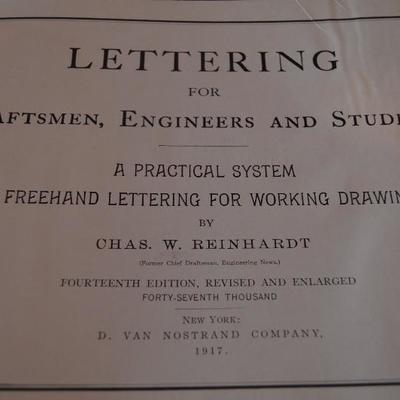

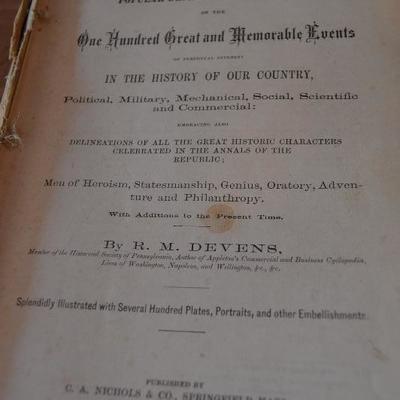

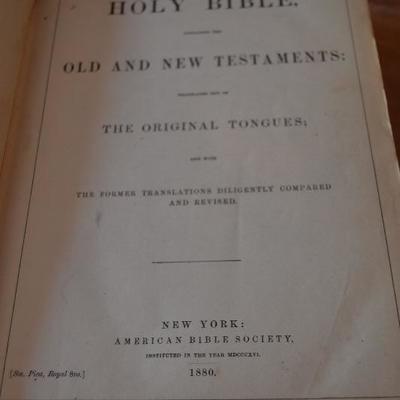

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 829 / 1073 -

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 830 / 1073 -

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 831 / 1073 -

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 832 / 1073 -

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 833 / 1073 -

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 834 / 1073 -

1). The official White House cookbook from 1906! Wow! 2). The National History of the War for the Union, Civil, Military and Naval (see typed note inside front cover!) 1900 3). Lettering for Draftsmen, Engineers and Students (1917) 4). Our First Century Being a Popular Descriptive Portraiture of the One Hundred Great and Memorable Events of Perpetual Interest in the History of Our Country, Political, Military, Mechanical Social, Scientific and Commercial: Embracing also the Delineations of All the Great Historic Characters Celebrated in the Annals of the Republic; Men of Heroism, Statesmanship, Genius, Oratory, Adventure and Philanthropy 1880 (This book might also be listed in the Guinness Book of World Record for the longest book title on record). 5) The Holy Bible Old and New Testaments 1880 Note: #2 and #4 are priced around $40-$50 each through rare book dealers. This edition of the White House Cookbook is still being printed. I couldn't find the value of the 1906 edition and the prices via abebooks (rare book dealer) range from $8-$106. #3 sells for about $8 through rare book dealers. 835 / 1073 -

A very large quilt top in excellent condition. We added Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 so it is fair to assume someone started this quilt in the 1940's or 1950's. Who knows, maybe she started sewing it in 1958 and finished it in 1959 about the time we added Hawaii and Alaska. Poor gal probably felt it was no longer valid and tucked it away for sixty years!!! Anyhow, we were 48 states from 1912 to 1959. Each state is represented and each state's flower is embroidered on a panel of the quilt. No reserve. 836 / 1073 -

A very large quilt top in excellent condition. We added Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 so it is fair to assume someone started this quilt in the 1940's or 1950's. Who knows, maybe she started sewing it in 1958 and finished it in 1959 about the time we added Hawaii and Alaska. Poor gal probably felt it was no longer valid and tucked it away for sixty years!!! Anyhow, we were 48 states from 1912 to 1959. Each state is represented and each state's flower is embroidered on a panel of the quilt. No reserve. 837 / 1073 -

A very large quilt top in excellent condition. We added Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 so it is fair to assume someone started this quilt in the 1940's or 1950's. Who knows, maybe she started sewing it in 1958 and finished it in 1959 about the time we added Hawaii and Alaska. Poor gal probably felt it was no longer valid and tucked it away for sixty years!!! Anyhow, we were 48 states from 1912 to 1959. Each state is represented and each state's flower is embroidered on a panel of the quilt. No reserve. 838 / 1073 -

A very large quilt top in excellent condition. We added Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 so it is fair to assume someone started this quilt in the 1940's or 1950's. Who knows, maybe she started sewing it in 1958 and finished it in 1959 about the time we added Hawaii and Alaska. Poor gal probably felt it was no longer valid and tucked it away for sixty years!!! Anyhow, we were 48 states from 1912 to 1959. Each state is represented and each state's flower is embroidered on a panel of the quilt. No reserve. 839 / 1073 -

A very large quilt top in excellent condition. We added Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 so it is fair to assume someone started this quilt in the 1940's or 1950's. Who knows, maybe she started sewing it in 1958 and finished it in 1959 about the time we added Hawaii and Alaska. Poor gal probably felt it was no longer valid and tucked it away for sixty years!!! Anyhow, we were 48 states from 1912 to 1959. Each state is represented and each state's flower is embroidered on a panel of the quilt. No reserve. 840 / 1073 -

A very large quilt top in excellent condition. We added Alaska and Hawaii in 1959 so it is fair to assume someone started this quilt in the 1940's or 1950's. Who knows, maybe she started sewing it in 1958 and finished it in 1959 about the time we added Hawaii and Alaska. Poor gal probably felt it was no longer valid and tucked it away for sixty years!!! Anyhow, we were 48 states from 1912 to 1959. Each state is represented and each state's flower is embroidered on a panel of the quilt. No reserve. 841 / 1073 -

Compact size, oil-free pump removes water down to 1/8 in. of surface Corrosion resistant, sealed thermoplastic construction Fully submersible Max. flow rate is 660 Gallons Per Hour; 360 GPH at 5 ft. of discharge lift 3/4 in. garden hose adapter at discharge For removing water from aquariums, clogged sinks, rain barrels 842 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 875 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 876 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 877 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 878 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 879 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 880 / 1073 -

In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 881 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 882 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 883 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 884 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 885 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 886 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 887 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 888 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 889 / 1073 -

Impressive rap sheet: Patents in clockmaking usually cover innovations to clockworks, the wheels and springs and escapements that together contribute to a clock’s ability to keep accurate time. In the case of Elias Ingraham, founder of the 19th-century Connecticut company that bore his name, the patents he applied for concerned the design of his cases. In fact, Ingraham won 17 patents between 1853 and 1873, all protecting the design of his clocks, most of which were made to hang flat on a wall or sit on a shelf. Ingraham was able to devote his attentions to the physical look of his clocks because the technology inside them was rapidly becoming a commodity. By the middle of the 19th century, spring-driven clockworks were replacing weight-based ones, which allowed clocks to be smaller and lighter. Clocks with balance wheels no longer needed to be so tall in order to accommodate a swinging pendulum. These innovations permitted Ingraham to focus on the look of his clocks to differentiate himself from his competitors. Which is exactly what he did. In 1844, he and his brother Andrew partnered with Elisha Curtis Brewster to form Brewster & Ingrahams. The firm would become E. and A. Ingrahams Company in 1852, Elias Ingraham and Company in 1857, E. Ingraham & Company in 1861, The E. Ingraham & Company in 1881, and The E. Ingraham Company in 1885. These minor name changes might seem overly fussy, but they provide the contemporary collector of antique Ingraham clocks with a sure way to date clock styles that were produced during multiple years. The first Brewster & Ingrahams clocks were called Gothics. Some had rounded tops, and some came to a point, with sharp "steeples" on either side of the clock’s dial. Competitors came up with their own variations on the steeple theme, as did Ingraham himself, whose embellishments upon his original included steeple clocks that were ringed with columns and adorned with rippled molding. Ingraham's banjo clocks, many in handsome walnut, were also fitted with springs. Ingraham shelf clocks ranged from painted timepieces richly decorated with mother-of-pearl to round Venetian and Grecian styles clad in rosewood veneer and adorned with gilt columns. Versions of these shelf clocks were also created for walls—the Ionic style was so popular that Ingraham made it from 1862 until 1924. In 1885, Elias’s son Edward took over the company and continued its innovation in clock cases. Double-dial wall and shelf clocks produced during this period told the time of day, the day of the week, and the month. As the 19th century waned, Ingraham made mantel clocks with Chinese motifs and carved dragon’s feet, as well as a number of patriotic clocks depicting war heroes like Admiral Dewey and stirring civic monuments such as the Capitol Dome in Washington D. C. But Edward’s chief contribution to his family’s company was a patent that covered the application of black paint to wood to create a shiny, marble-like finish. These clocks proved very popular for the venerable firm—some 200 designs were produced until the 1920s. Ingraham continued to produce wooden wall and mantle clocks until World War II. Between the wars, the company also diversified into pocket watches and wristwatches. But in 1967, Ingraham was sold to McGraw-Edison, which converted its clock factory in Bristol, Connecticut into a production facility to make fuses, which by then was a more profitable enterprise than making clocks. 890 / 1073

Photos 801 - 900 of 1073

Per page: